In the past, a long, long time ago, everything was better — Video On Demand was still ad-free, blue verification checkmarks had to be earned through hard work in the public eye, and video portals served the credo “Broadcast Yourself” instead of being clocked continuous advertising broadcasts.

One way or another, you could certainly complain, but (to be honest) you can just leave it alone. 😉 But what's exciting is that digital media, social media and online platforms, which have been described as a service future of entertainment and discourse, are making a U-turn. The big egalitarian social bazaar called the Internet, from John Perry Barlow still fantasized as “Home of Mind” (in its rather poorly aged one”A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace“), seems to be regressing to its roots. With that in mind, you ask yourself whether something can develop in such a way that it takes a wrong turn, goes around in circles and ends up back at the beginning. Are digital spaces currently returning to their former form? Let's talk about that.

In fact, there is currently a certain end-time atmosphere in digital luxury, As The Atlantic has already stated. Facebook continues to stagnate, Twitter (or X) has been desperately trying to keep itself alive since the takeover of Musk — we too have long since turned our backs on 55 account X — and more and more advertisers are withdrawing from various platforms. A crisis situation which not only leads to considerable financial losses, which in turn causes huge layoffs, but is also making waves: Online magazines, which are still flourishing on Covid and are known to be strictly dependent on any platforms, must also ask themselves whether they are prepared for a mass decline in digital reporting, such as the print before them, According to The New Yorker. Dark as it may sound, the plausible idea opens up that social media, as we've known it for years, could come to an end.

In keeping with this, Ian Bogost has already stated:

A global broadcast network where anyone can say anything to anyone else as often as possible, and where such people have come to think they deserve such a capacity, or even that withholding it amounts to censorship or suppression—that's just a terrible idea from the outset. And it's a terrible idea that is entirely and completely bound up with the concept of social media itself: systems erected and used exclusively to deliver an endless stream of content.

Many of us are certainly familiar with the sporadic annoyance about such things. This gradual loss in value is Cory Doctorow affectionately as “Enshittification”. 💩

Here is how platforms that: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

According to Doctorow, “enshittification” should be the inevitable consequence of the “two-sided market,” in which a platform sits between buyers and sellers and holds both hostages of each other, skimming off an ever larger share of the value that is conveyed between them. The result is a place where you don't like to be as a user, company or advertiser and suddenly, for example, a shop is integrated into the Instagram app that no one actually wants to use — because there are far more trustworthy shopping platforms for that.

Even though every farewell is sad, this presumed end is perhaps an opportunity to create a better cyberspace, closer to the revolutionary tone that Barlow set in 1996. But in order to know where to get started, the first question is where exactly it went wrong.

Let's row a step back to when the platform stops being good to its users after Doctorow:

A desirable platform status can usually be attributed to that social media is primarily free. Revenue comes from advertising and usage data. The more users, the more attractive you are as an advertising partner and the more data is available. Pretty basic, everyone is happy and satisfied — hurray! 🎉

A coherent system, with the fundamental flaw of said scalability, because, of course, platforms want to grow. If there is no growth and revenue is also falling due to an oscillating economy, Is there a fairly obvious problem: Red numbers. Put in a somewhat simplified way, of course.

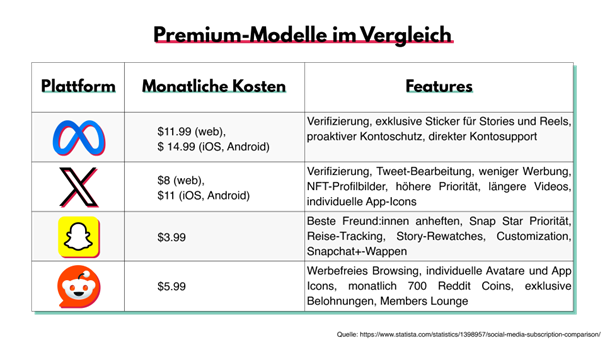

A problem that premium models introduced on this basis should address: The paid alternative to the basic premise. The alternative solution of several small advertisers should be mentioned, but As Gene Marks reported for The Guardian, this is accompanied by sad results, where bots primarily interact with their own product. Ergo not worthwhile for advertisers.

Similar methods can also be observed on Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Co. for similar reasons, which do not offer premium models (after all, the service offered here is also not free), but increasingly rely on advertising. Prime Video is already running commercial breaks during streaming — the reason for this is that this continues”to invest in compelling content for a longer period of time“— and Netflix is betting on a cheaper standard subscription with advertising For, compared to the other options, cheap 5€. A very popular option so far, despite initial difficulties. The aim of this subscription is a new pool of subscribers and parallel income from advertisers.

Netflix's co-CEO Greg Peters also explains that the goal is increased scaling and a switch to a more attractive advertising subscription. The transparency of the platforms is commended, of course, as people are well aware that if these measures are not adequately justified, they will give more impetus to cancel than to use the service. We want to remain competitive in measures that are also a necessary evil. However, the result remains a poorer user experience, a less attractive platform and not to forget as a symptom of the previously mentioned problem of limited scaling. Suddenly you're strangely close to the actually antiquated free TV again.

Within this problem, streaming services are in a different sector than social media, because they produce actual content, while social media depends on its users in this regard. No tweet has been nominated for an Oscar so far. 🎬🏆 Streaming services therefore provide fundamental value, for example by offering access to films or series. This makes social media more difficult. The content produced by users is fundamentally different from, for example, a new film by Martin Scorsese — a really unfair comparison Which, however, plays a role when content is known to be king.

Social media is therefore faced with the big problem of providing an impulse that is decisive enough to actually pay for such services. Completely without implemented cultural assets. As the direct comparison shows, the platforms have had a hard time doing this so far:

Ad-free use is perhaps the most attractive feature here — mind you, on an Internet Where around 40% of all users have installed an ad blocker. It's an unsatisfactory omen. Verification was also hoped to be attractive, as it had always been intended for the select few. The fact that this status is immediately a thing of the past as soon as acquired was somehow disregarded. Of course, you can't completely deny the benefits, especially for smaller companies, verification can be important, but the average users only communicate with this to pay for the chosen platform, which may not be perceived as cool as hoped for. Of course, there would also be digital cosmetics. Ok. Exciting for those for whom more than 3,000 emojis aren't enough.

The corresponding question is whether this is really all that social media can offer its users, in addition to the free content that is essential for survival. These are the ideas of many bright minds and digital pioneers, experts in their fields, who are far more familiar with their subject matter than most of us — and when their ideas are based on comparatively weak features In this case, the answer may simply be no.

Oh woe.

In the wake of all this, social media is a long way from what kept you on these platforms. The New York Times describes the following dispute:

Instead of seeing messages and photos from friends and relatives about their holidays or fancy dinners, users of Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Twitter and Snapchat now often view professionalized content from brands, influencers and others that pay for placement.

Zizi Papacharissi, Professor of Communication Sciences at the University of Illinois-Chicago, comes to the following conclusion: “Platforms as we knew them are over. They have outlived their utility. “So maybe it doesn't even matter the features themselves, which various premium models offer. If the platforms simply become less important in our lives year after year, this is the biggest counterargument to the payment service that you could think of.

But what would be the alternative? As I said, the eventual end of various platforms does not mean the end of the Internet or of social media in general. Experts seem to be largely in agreement on this and the good news is that even though you may have to say goodbye, the future of social media and the like sounds quite promising as soon as it is no longer synonymous with big tech.

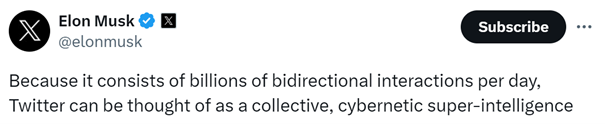

When Elon Musk bought up the former Twitter euphoric, he quickly announced his ideal of this platform: A collective, cybernetic super-intelligence — democratizes, completely without feudal lords and vassals, a melting pot of ideas.

It is once again the ideal that Barlow has already announced: The centralized marketplace. The extent to which Musk failed because of this would be another topic in itself that you don't have to start now. The only important thing is the persistence of the idea of a higher-level platform, similar to the Chinese Wechat. An idea with which we According to Ethen Zuckerman — Professor of Public Policy at the University of Massachussetts — have to finally settle the bill; it is “Crazy Silicon Valley Logic” and is not even worth striving for, but that's exactly why it's important to mention.

Here is what experts say probably It's going to happen.

Experts and CEOs already have ideas about which direction things could go. Mark Zuckerberg wrote in 2019 that Facebook's fastest-growing sector is various, small communities in which thematic and hermetic communication takes place. Jack Dorsey, former Twitter founder, is also in favour of decentralizing social media, which enables users to control content, and is therefore now mainly on Nostr, a platform based on this. As I said, only Musk sees things a bit differently, but that's nothing new.

We can currently observe at least a certain cultural migration of the Internet — away from the omnipresent marketplace of the online metropolis, we are emigrating to smaller, village-like digital spaces that meet our interests more precisely. As an example, think of something like our personal favorite LinkedIn, which as a platform is dedicated to one topic in particular and enables discussion and exchange on this subject. Of course, the return to smaller niches on the Internet is also a regression to the MySpace era of the Internet, but decided by users, not an overarching platform, as before. Reset and try again. An idea whose potential should definitely not be underestimated, mind you. The New York Times cites this as an example:

One major benefit of small networks is that they create forums for specific communities, including people who are marginalized. Ahwaa, which was founded in 2011, is a social network for members of the L.G.B.T.Q. community in countries around the Persian Gulf where being gay is deemed illegal. Other small networks, like Letterboxd, an app for film enthusiasts to share their opinions on movies, are focused on special interests.

This is not only cheaper and more efficient and enables a large number of smaller, veritable companies that can offer a self-contained business model, but public discourse could also benefit from this. The basic idea of a large, centralized place where a wide variety of ideas would be exchanged sounds great in theory, but it became apparent quite quickly that our brains are not designed for this — possibly not even the platforms themselves. No substantive discussion over 280 characters has ever arisen on Twitter. Even populism, which can easily flourish on centralized platforms, As Mai Thi Nguyen-Kim (also known as MailAB) recently explained in her related publicity stunt, This could be limited by this. The Internet likes to hang on at its whistle and it's certainly not controversial to say that it's just not nice. Not infrequently due to banalities. This is another reason why this emigration is demonstrably taking place.

Of course, none of this is set in stone. The platforms that Big Tech provides all offer their respective advantages, otherwise we wouldn't be spending any more time on them. However, the signs from the enshittification social media crisis point in one direction — and if, for many of us, online presence has become a significant part of our own lives, it is of course desirable to help shape it and find it enriching.

Perhaps this development will be delayed; perhaps this process has already started. At least this was followed by the message Reddit would now go public. In any case, the Internet is currently living — even in the course of generative AI, which would be worth a contribution in itself, but here truly goes beyond the scope — the most exciting transformation since the days of its digital cultivation.

What do you think? A storm that is passing by again or will social media change significantly in the future?

For further reading:

Do you have a question or would you like to find out how we can work together?

Feel free to contact us here or via linkedin with us — we'd love to hear from you